- Home

- Thomas Cullinan

The Beguiled Page 4

The Beguiled Read online

Page 4

There was an old copy of the Southern Illustrated News on the table. I opened the newspaper on the settee and then proceeded to lift our prisoner’s legs up on to it.

“I believe there are some poems by Edgar Allan Poe in that newspaper which Miss Harriet is desirous of saving,” Edwina commented.

“She’ll be glad to sacrifice the newspaper, I’m sure,” I said, “rather than the settee. Be quiet now and give me a hand, one of you, while I straighten him out.”

He was only barely conscious then, but I’m sure he heard us. His eyes moved slowly from Alice to Edwina and back to me, asking silently for help. I really and truly felt sorry for him then, the way the very life was draining right out of him. His face was gray behind the freckles wherever it wasn’t covered with soot, and his lips were turning as blue as his eyes.

Alice poured a bit of water in a glass and brought it to him, but he couldn’t open his mouth enough to drink it. When Alice tried to pour it in, he just slobbered it out like a month-old infant.

“Try it this way,” Edwina said. She dipped her handkerchief into the water and then gently squeezed the water drop by drop between his lips.

“That’s good material, isn’t it?” I asked her.

“It’s Chinese silk,” she said. “My father brought it back from Shanghai after one of his trading voyages.”

Well, I privately doubted that her father had ever been on any voyages to China or anywhere else of any great distance other than, if the stories were true, some frequent trips up and down the river before the war. I don’t spread rumors usually, but one of the girls who didn’t come back to school this year—perhaps it was Leonore Fairchild or Martha Willis—has stated as a positive fact that for several seasons Edwina Morrow’s father had presided over a card game in the main salon of the Memphis Queen and had been called out and caned several times and once thrown into the Mississippi as a result of irregularities arising from those activities. Be that as it may, however, the handkerchief was definitely rich goods and I must admit that I would have thought twice about it before soaking it in water to comfort a Federal soldier.

“That was very clever of you to think of that, Edwina,” I said. I usually try to compliment her whenever I can, though the Lord knows there’s seldom much opportunity. “Now don’t give him the water too fast,” I told her, “or he may go off in a choking fit even before he bleeds to death.”

Amelia Dabney came back in then, dragging old Mattie who had an apron full of peas that she had been shelling. Poor Mattie took one look at the figure on the settee and then let out a terrible shriek and scattered those peas all over the living room.

“You chil’ren have brought destruction in this house,” she cried. “Take him back! Take that critter back where you found him. Let his own take care of him. He ain’t no concern of ours.”

“There were none of his own around,” Amelia said defiantly. “He was all by himself.”

“Take him back anyway,” Mattie insisted. “Take him away off somewheres and let him die a good ways from this house. Don’t let him pass away in this living room so’s the Yankees can come around here bangin on our door and accusin us of murderin him.”

“Nobody’s going to accuse us of anything, Mattie dear,” Alice said soothingly. “Nobody knows he’s here but us . . . and the Lord. The Lord probably sent him directly to us intending for us to take care of him. That means all of us, Mattie, you too.”

That was enough to settle Mattie down. I believe the mere suggestion that the Lord was asking her to take a hand in His affairs would have been enough to send Mattie marching off to face those very cannons that kept rumbling their unearthly chorus off there in the woods.

“Where’s Miss Harriet?” Mattie asked, venturing a closer look at our prize.

“She’s napping, I guess,” said I. “Marie has gone to fetch her.”

“If anything is gonna be done for this boy, it’s gonna have to be done mighty quick,” Mattie said as she felt his brow. “Though I wouldn’t be surprised if it warn’t too late already.”

Well, I guess we all burst into tears at that, Alice and Amelia and I, and even Edwina, I noticed, managed a drop or two.

“Now, now girls,” I told them. “Compose yourselves. It’s only natural to feel some pity for the fellow, but after all, he’s no worse off than if Amelia hadn’t found him.”

“That’s right,” Amelia said as a new thought came to her. “Or perhaps that’s part of the Lord’s will too. Maybe we’re not supposed to be able to do anything for him. Maybe I was just supposed to find him and bring him here and that’s all.” Dead or alive, he was still a forest specimen to Amelia, a rare specimen which she had found all by herself.

“What’s keepin Miss Harriet?” said Mattie, joining in the weeping. “What’s keepin that poor lady?”

“She’s coming now,” announced little Marie Deveraux re-entering the living room. “She only waited for a moment to fix herself up a bit. I saw her pinching her cheeks to bring the color to them and she also put some lamp black on that gray streak in her hair. I expect she figures it isn’t every day we get a man in this house.”

Harriet Farnsworth

As I recall now, it took some moments before Miss Marie Deveraux’s news began to penetrate my numbed mind. I had taken to my bed with a severe headache after sewing class and at first I thought what she was telling me was just some childish nonsense of her own invention. The younger girls especially are not adverse to playing little tricks on me occasionally, knowing they can count on my good humor. I will tolerate all sorts of silliness which my sister would not countenance for one instant. Martha claims that this laxity on my part causes the girls to lose respect for me. That’s possible, of course, but I think sometimes they like me better for it.

“All right, I’ll have a look at this prisoner, Miss,” I said, arising. “And if it is only more of your foolery, you shall go without your dinner.”

I tidied myself a bit and threw the black lace mantilla over my shoulders—the mantilla Father had brought home from the Mexican War—and then I followed the impudent little Miss Deveraux down the stairs.

As a matter of fact, I did half expect to find some visitor in the living room, some relative of one of the girls—a brother possibly, or a father, stopping by on his way to the battle. That was in furious progress now by the artillery sounds, but still a mile or more away from us—much too far, I thought, for any wounded straggler from it to come wandering through our woods.

But one had. And he would never wander farther by the present look of him.

“He’s still alive, Miss Harriet,” Alice Simms said, as though saying it would insure it. “You see how he clouds my mirror when he breathes on it?”

Over his half-open mouth she held her cheap little pocket glass—a relic of her unfortunate mother—and then presented it for me to examine.

“Blood is still seeping from the wound in his leg, too,” said the practical Emily Stevenson. “I believe that means his heart is still functioning—though I have felt his ribs several times and can detect no tremor.”

“This sort of thing is quite beyond my experience,” I told them. “But of course we must do whatever we can for him, at least until Miss Martha comes home.”

I could imagine what Martha’s reaction was going to be when she set eyes on him. I knew what she would say about the safety of our charges and this breach in the walls of our defenses. Nevertheless, until she did return, the responsibility was clearly mine, and I resolved to do my best to handle it.

“One of you girls run up to my room and fetch my sewing basket. Mattie, is there any old cloth that we can spare?”

“There ain’t no cloth at all that I know of,” Mattie declared. “I want to dust around here any more, I got to do it with corn husks. You know Miss Martha has given most all of our sheets and pillow cases to the ladies who been collectin them

for bandages.”

“The damask tablecloth in the linen cupboard then,” I said. “Get that, Mattie.”

“Your Grandma brought that from the Tidewater place,” Mattie cried horrified. “And the Lord knows how many years it was in the family before that. You ain’t gonna stain that tablecloth with enemy blood, Miss Harriet? Miss Martha sure ain’t gonna like it.”

“Fetch it,” I said. “I’ll explain it to Miss Martha when she comes.”

I am sometimes surprised myself at how authoritatively I can act in an emergency. Of course, it helps if Martha isn’t around.

Mattie brought the cloth with no further protest and Amelia came back downstairs with my sewing basket. I took my scissors, breathed deeply, and began to slit his trouser leg.

It was ghastly. From the ankle nearly to the knee it was one long lacerated trench with the bone exposed at the calf and pieces of dark metal embedded in several places.

“Miss Martha will have to ’tend to this,” I said between my teeth. “I’m not qualified to fool with this. Any of you girls who are about to faint, go elsewhere and do it.”

I cut the tablecloth in strips and bound the leg as tightly as I could above the knee, getting Emily who was the strongest to tug at one end of the cloth while I pulled on the other.

“That ought to stop the bleeding somewhat,” I said, “if there’s any blood left in him.”

Then I went to the wine cabinet. Martha generally keeps it locked because in the past we have had one or two girls who liked to filch a sip or two of sherry in the afternoon, more out of mischief, of course, than anything else. Luckily I knew a way of opening the cabinet with my scissors blade and more lucky yet, inside the cabinet and hidden behind the sherry there was half of a bottle of plum brandy which Marie Deveraux’s father had sent to us two Christmases ago and which I had forgotten about completely.

I poured a small glass of brandy for myself to stop my hands from trembling, then brought a bit of it over to the poor fellow on the settee. The girls stood and watched with great interest as I ever so gently poured a drop or two of brandy between his lips.

“He’ll only choke on it,” Edwina predicted. “That’s what happened with the water when Alice tried to give it to him.”

“Brandy may have a different effect on him,” said little Marie. “I believe he’s an Irishman from his way of talking and many of those people have a great liking for alcoholic spirits. I know Mister Patrick J. Maloney, who was our overseer at home for a brief period before the Yankees invaded us, used to say that he had nine lives like a cat and that in case of death, he could be revived with one of my Daddy’s special toddies which he dearly loved. I’m only sorry you’ve never tasted one of those toddies, Miss Harriet. I really believe you would enjoy them too.”

“A toddy is not a lady’s refreshment,” I told her sharply. I thought to say more but she seemed so guileless, as she always does, that I let the matter drop. It quite astonished me the way those girls could just stand there gazing with such fascination at that apparently dying boy and his terrible wound. When I was a young girl, the mere sight of a finger pierced by a thorn was enough to make me swoon, but these students of ours seemed to have no such sensibilities at all. That, I think, is one of the uncalculated evils of our times—the way these years have hardened our young ladies.

I poured another small glass of the plum brandy, swallowed a tiny bit more of it myself and then, again very cautiously, fed the rest of it to the boy. If it was doing him any good at all, there were as yet no visible effects, but at least he was keeping it down.

“Stand aside now, girls, if you please,” I said. “Let the poor thing have what air there is on this stifling day. If he’s going to die, let him be as comfortable as possible until it happens.”

They obeyed me and did move back a bit. Marie tittered nervously and Emily reprimanded her, Amelia and Alice looked to be the most woebegone, the first, I guessed, because it seemed she might be losing her prize trophy, and the second because she was beginning to think, like her unfortunate mother, that the loss of any man diminished a woman’s world. I wondered idly if either Alice or her mother had ever heard of John Donne.

All of the girls had tears in their eyes, I noticed now, including Edwina Morrow, one girl in whom I had never expected to find any pity. She saw me looking at her then and quickly blinked away the tears. And then smiled and winked at me.

Edwina Morrow

The drunken old busybody . . . the stupid old tippler! I suppose she thought I wasn’t aware of what was going on but she was wrong. As far as that goes, I’m sure all the girls in the school knew of Miss Harriet Farnsworth’s frequent trips to the wine cabinet and, formerly, to the cellar where the larger stocks of wine were kept. I say “formerly” because I expect the supply that Miss Harriet’s father put in years ago must be exhausted by now. In any case, I haven’t seen Miss Harriet sneaking down there lately, but of course that might be because her sister has put a new padlock on the cellar door and Miss Harriet as yet hasn’t figured out a way to open it. Not that the wine supply or lack of it affects the students in any way, since none of it was ever served to us, except occasionally during Christmas holidays to those who didn’t go home.

One Christmas Eve, as a matter of fact, when Miss Harriet and I were sitting alone by the fire in the parlor, after Miss Martha and old Mattie had gone to bed, Miss Harriet and I consumed quite a bit of wine together. As I recall, that was the first winter of the war. I was fourteen at that time and I suppose Miss Harriet assumed it would be an easy thing to loosen my tongue with wine, so she could learn all the things about me which she doesn’t know, and never will know!

She made one great mistake on that occasion. One thing she didn’t realize about me was that I had learned to drink wine at a very tender age. When I was only six or seven, my father used to hold me on his knee in various clubs and taverns and in the salons of various steamboats from St. Louis to New Orleans, at which times he would pour wine into me as though it were my mother’s milk. This was partly out of kindness, I suppose, and partly in an effort to quiet me so he could get on to more interesting affairs.

At any rate, I was still clear-headed on that Christmas Eve long after dear Miss Harriet had begun to nod and slur her words and spill her sherry in her lap. She wanted me to tell her of my past life with my father—where my mother was and about my family generally—all the facts which she and her sister had been unable to learn in previous questioning. Again I told her nothing, but I added considerably to my store of knowledge about her, which knowledge I will be very glad to reveal to anyone who seeks it. And there will be no charge for this information.

All the Farnsworth sisters know about me now is practically no more than they knew on the day I came. That was that my family name was a good one, that my letters of recommendation (including one signed by an important governor and another by a gentleman who is now a member of Mister Davis’ cabinet) were excellent, no matter how the letters were obtained, and the quality of my money could not have been improved upon.

My school accounts have always been paid in advance, which is something I dare say cannot be said about the accounts of the other girls in this place. When I came here four years ago, I brought sufficient money to take care of my needs amply for much longer than I ever intended to stay. When I entered this school for the first time, my Indian beaded handbag was filled to the brim with Federal gold coins, a kind of species of which, I soon found out, Miss Martha Farnsworth was particularly fond.

Therefore my credentials being of the finest, I am constantly deferred to in this school. Although the girls all hate me and the Farnsworth sisters love me little more, still I am treated here with the utmost civility, at least by Miss Martha and Miss Harriet. When there is an extra serving of Mattie’s pudding left at dinner, or an extra rasher of bacon at breakfast (I am speaking of the past now since we have not had any bacon for some time), i

t is generally offered to me before anyone else.

Oh yes, Miss Martha is definitely partial to the sight and sound of gold coins. The only times I ever see any animation in her eyes are these occasions twice a year when I drop my little stack of double eagles on her desk. It seems to be the one thing in life that gives her pleasure. “There, Miss Martha,” I sometimes say on those occasions. “I hope you are not too patriotic to accept this Yankee money. If you are, I will be more than glad to go to a store or bank and try to persuade some gentleman to exchange with me for Confederate paper. Or perhaps you’d rather wait until my father has the opportunity to send me some of our own legal tender.”

“Oh no, Edwina,” Miss Martha will always answer. “I won’t put you to that trouble. This will serve our purposes as well as any other.”

This patriotism is a tricky thing these days, you see. She really never knows when I bring it up whether I am mocking her or not. Of course, I am sure Miss Martha is no more patriotic than some old cow in a pasture. In fact, she probably doesn’t even care who wins the war as long as the outcome has no effect on her personally. What she would like is to have the thing done with, one way or the other, so the enrollment can return to normal and once again the money will pour into the Farnsworth School.

I know Miss Martha, as well as the other students here, would give anything to know how much money I have left. I’m sure that on one or two occasions some people have searched my room. This was done very cleverly, of course, and both times everything was almost restored to its proper place, except the first time the position of a book on my night table was altered and the second time a black thread was removed—a thread which I had suspended from a knob on a cabinet drawer.

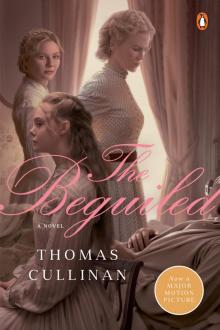

The Beguiled

The Beguiled