- Home

- Thomas Cullinan

The Beguiled Page 5

The Beguiled Read online

Page 5

Anyway, there aren’t enough of my Federal double eagles left now to pay for another year at this place, but that doesn’t matter. I have settled with the old crows for the present term and long before the leaves have fallen, my father will be here to take me away.

They know nothing about me and my father, but I know a great deal about them. I know of Miss Harriet’s problem with the wine and Miss Martha’s greed and many other things about their lives now and in the past. I have heard the quarreling in the night. I’ve heard Miss Martha’s bitter accusations and Miss Harriet’s weeping. She weeps, like all the weak people in the world, for the lost days, for the way things once were and will never be again.

She turned away from the wounded Yankee on that first afternoon and looked at me with a smile of satisfaction. I couldn’t imagine what was on her mind until I realized she must be thinking I was shedding tears myself, for the soldier presumably. Miss Harriet was happy because she thought she had found another bleeding heart.

Well, once again she was wrong about me. I was not weeping out of any pity for the Yankee. If one were to begin bewailing the wounded and the dying, even those who had been struck down on one solitary day, there would be no end to weeping. I didn’t know this fellow. He wasn’t wearing the uniform I was supposed to be supporting, and for all I knew, he deserved what he got. At least that is how I felt, as far as I can remember, on that first afternoon.

I doubt very much that I was weeping at all on that day. It was probably only some trick of the sunlight from the garden which caused Miss Harriet to think so. Or even if my eyes had watered slightly, it was very likely the result of some passing thought about my father. In a way, the Yankee reminded me of him. My father is long-limbed and thin, and sometimes, after a sleepless night, very pale too, like this fellow was. In fact, there was a time—not so very long ago either—when my father didn’t look much older than the Yankee on the settee.

“He would be far better off if he died right now,” I remember thinking, “and was free from all his misery. I wish him well. I wish he would die.” This sorry mood and the sunlight caused my eyes to fill up again and so to avoid giving Miss Harriet any more pleasure, I turned and left the room.

I went out on the front portico and sat there alone, considering my way of life and how it might, conceivably, in the near future take a turn for the better. I took out my Chinese silk handkerchief to wipe some perspiration from my brow and found it still wet from some water I had spilled on it. The handkerchief belonged to my father—a souvenir of one of his many lady friends. I rolled the useless little piece of cloth into a ball and threw it into the forsythia bushes beside the porch.

The artillery fire was continuing in the woods and there was a great deal of smoke in that direction, covering the whole eastern and northeastern sky. It occurred to me that I was not the only person with trouble in the world. Each rumble of the cannons, each swirl of smoke, was a sign of great trouble, starting at the spot in the woods where the metal landed and spreading like ripples in a stream to villages and towns and solitary lonely houses all over the land. Perhaps the trouble of the wounded boy inside would spread and infect people far away from here—a mother possibly, or a sister, or a sweetheart. I wondered if he had a sweetheart.

I also wondered vaguely if anyone would be concerned if I died. If, for instance, a misguided shell should fall on the school and kill me, would anyone really care? Would my father care—or did he have more pressing problems of his own?

Time passed—perhaps an hour—while I was thus occupied. Just before sunset, I saw Miss Martha with the pony and cart turn off the Cedar Hill road and start up the school drive. “Here comes the cannon ball that will decide the Yankee’s fate,” I thought. “His life is in her hands.” Subsequent events proved that was only partly true. His life was in all our hands, as ours were in his.

At any rate, I decided I’d walk down the drive to meet Miss Martha and tell her the news.

Martha Farnsworth

I had warned Amelia Dabney a hundred times to stay out of those woods. Now, I decided, there was nothing else to do but punish her for this latest act of disobedience.

“Will you ask her parents to take her home?” asked Edwina Morrow. She had climbed into the cart, uninvited, and was riding beside me to the house.

“I believe that will hardly be possible at the present time since her home is in a battle zone.” I had no wish to discuss the matter with Edwina.

“That’s true,” she said, determined to continue the conversation. “I’d forgotten that. As a matter of fact, it’s my impression that Amelia has not heard from her family for some time, as I have not heard from my father.”

It was my impression that her father might just possibly have been detained by the authorities for some illegal speculations in cotton. At least, I had seen his name in a Richmond newspaper several weeks before—we no longer receive the papers at the school, but this was a copy owned by Mister Potter at the crossroads store—in which her father was mentioned as one of several people being questioned by a government commission set up to look into such activities. However, the girl could know nothing of this and I was not about to tell her.

“Also, I imagine in times like these, Miss Martha,” she went on, “with all your additional expenses—food prices being so high and all, you would naturally be reluctant to expel any paying student—even an irresponsible little person such as Amelia Dabney.”

“There is no present question of expelling anyone,” I told her sharply. “And if there were, the school would not be dissuaded by any financial considerations.”

I knew from three years’ experience it was not a wise thing to enter into debate with Edwina Morrow. She apparently takes a malicious pleasure in twisting anything I say to fit her own purposes—childishly evil whims for the most part—born of her own loneliness, Harriet insists. Born of the devil, I am more inclined to think.

“What do you plan to do about the Yankee soldier?” she asked now.

“I plan to do nothing,” I said, “until I can get in touch with some of our own troops and deliver him up to them.”

“It may be some time before you can do that,” the girl said. “The way it looks now, our boys are otherwise occupied.”

She was right in that respect. It looked as though they would continue to be occupied for quite some time, considering the sounds and conflagration which seemed to be advancing nearer to us. “If the wind doesn’t change before long,” I thought, “we may have much more to worry about than one wounded Yankee soldier.”

The thought of fire reaching our buildings had been with me since the last battle, and before I was ten minutes on the road that morning, I was sorry I had decided to go for supplies. There had been troops moving eastward on the turnpike the afternoon before—hordes of them by the dust—and in the morning, still more of them even on the Cedar Hill road beside our place. That road, of course, is on private property where it crosses our land, though we’ve never interfered with its use by anyone on legitimate business.

That used to be the old logging road when my father was cutting oak and cedar out of our woods. Most of the best timber is gone now, though we still have a few good trees. To the east of us on the other side of Flat Creek, it’s all scrub pine and sweet gum and thorn bushes, whatever wasn’t burned away during the battle which began that first week in May of this year or wasn’t consumed during last year’s fighting around the old Chancellor place.

At any rate, the firing had begun while I was still on the Cedar Hill road before I reached the turnpike. I had hoped to be able to cross the Pike without incident and continue down to the old Plank road which, being narrower, might be hoped to contain less military traffic. However, the firing to the east caused such confusion and piling up of troops at the crossroads—with some of those on horseback trying to move more rapidly down the center of the Pike and some of those marchers on the sides d

eciding to slow down instead of speeding up—that it seemed we might be isolated from Potter’s Store for the remainder of the summer.

I pulled up as close as I could to the edge of the turnpike and called out until I got the attention of a boy who wheeled his mount against the traffic and rode across to me. He was about seventeen, trying to grow a beard, and as brown and bony as his horse.

“Lieutenant Depew, Sixth Alabama,” he shouted. “Can I be of service, ma’am?”

“I have to get across this road,” I said, “immediately.”

“No civilian’s allowed on this road today, ma’am.”

“I don’t want to get on the road—I want to get across it to the Plank road.”

“You can’t go down there either. There’s Yankees a couple miles to the east of here. They’ve crossed the river and are headed for Richmond.”

“Well that’s your business,” I told him. “I have my own to attend to. Who’s the general in charge of you soldiers?”

“We got a lot of ’em, ma’am. General Rode, General Battle, General Ewell . . .”

“Dick Ewell will do. You tell him that Miss Martha Farnsworth wants permission to carry out her urgent business. Tell him Miss Farnsworth begs to be remembered to him because she thinks she had some young lady cousins of his in her school one time.”

There was a momentary break then in the line of troops. I gave the pony a slap of the reins and moved across the road.

“Ma’am . . . come back here, ma’am,” the boy shouted.

“You just tell General Ewell what I said,” I called back. I was across the Pike by then and moving down the Cedar Hill road on the other side. I reached the Plank road without any more trouble, but found that highway nearly as congested as the Pike. It was jammed with the men of General Hill’s Third Corps who advised me, with accompanying profanity, that there was a battle now in progress at the Brock road crossing and that they were moving up to it. I told them I wasn’t going quite that far so they let me fall in behind one of their ammunition wagons.

It took a couple of hours, I guess, because the Plank road is narrow, with boards only on one side. The heavy wagons were constantly slipping and sliding in the mud and the mounted men kept trying to ride around and in between the marchers. It was noon or after before we reached Potter’s store. I turned into the yard and found Mister Potter outside putting up his shutters.

“You can’t close just yet,” I told him, tying the pony to his porch. “You’ve got a customer.”

“I haven’t the time to argue with you today, Miss Martha,” said Mister Potter nervously. “Grant and his whole Potomac Army are crossing the river right now up at the Germania Ford. I can’t leave this place open for them Goddam German mercenaries to loot.”

“Please watch your language,” I told him. “I don’t know what you’re so worried about anyway. Why should the Yankees take anything from you? Those people are probably carrying more in each of their wagons than you’ve got on all of your shelves.”

Some people in this locality declare me unpatriotic and unsympathetic to our cause because of sentiments like these, but I affirm it’s only being realistic. The Yankees have all the goods and all the money and and therefore, it seems evident to me, they will eventually win the war. Money is your great and ultimate weapon. With money you can buy steel and gunpowder and salt pork and all the courage you need.

I said these things in eighteen and sixty-one and I do not hesitate to say them now. Nowadays I don’t see how anyone can be uncertain of the outcome. It is no longer a question—if it ever was—of who will be victorious, but only how much longer we can continue to bleed. (The same thought occurred to me later when I saw the Yankee in my living room and the results of Harriet’s poorly applied tourniquet on my needlepoint settee.)

Well, if I cannot be sensible and popular at the same time, then I will always choose the virtue rather than the friends. We prefer to live in isolation at our school anyway. We’ve managed by ourselves until now and with the help of the Almighty—Who makes less demands than one’s neighbors—will continue to do so.

Of course it is one thing to have sensible convictions and another to fly them from a flag pole. I realize that many of our girls have lost near relatives in the war—I lost a brother myself—and it sometimes causes grief to think that dying serves a purpose. Therefore, as much as possible, I avoid entering into any discussion of military events with the students—or even with my sister, who is often as ostrich-like about the situation as they are.

As I have told Harriet lately, our prime concern right now must be to keep the school in operation, so that we may capitalize on the resurgence of the spirit that is bound to follow the ending of the war. When normal travel and communication is once more established in the South, I expect Farnsworth School to be crowded to the doors. We may even have to build an addition to the house and hire another teacher—perhaps some recently widowed or fatherless young lady who, under the circumstances, might be willing to work for very little or no money—perhaps merely for her room and board.

Money . . . if my father had only managed to save more of it, if my mother had not wasted it on my brother, Robert, if my sister had not spent her portion on a foolish flight to Richmond at the age of eighteen—to marry a certain New York gentleman named Howard Winslow, she thought, but found out differently after Mr. Winslow had departed with some eighteen thousand dollars of Farnsworth money. If all of these things had not taken place, it might never have been necessary to start the Farnsworth School. Not that I can honestly say I have ever regretted that part of it. In a certain sense, I gain a great deal of satisfaction out of forming, and sometimes reforming, young lives.

These feelings have made me less bitter toward my sister in recent years. Harriet usually does try her best to carry out my wishes and if she does not always succeed, it can be blamed on weakness rather than on any perversity in her character. Harriet is not an unintelligent person; she is just not wise in the ways of the world.

I have never discussed the Howard Winslow affair with her at any great length. I was too angry when it happened and in late years I haven’t really cared. I don’t know the exact circumstances of her parting with the man—whether she gave him the money or if he took it from her by force—although that would scarcely seem necessary, considering my sister’s gullibility. I am sure that she expects Howard Winslow to come back some fine day, riding on a white horse and prepared to carry her off to some golden land of romance.

Thoughts of that nature—and the little wine I sometimes allow her—keep her in reasonable control. She seldom leaves our grounds, except to attend Saint Andrew’s on Sunday, although I’ve discontinued our church going while the war remains in this neighborhood. Well in spite of all, Harriet is a good teacher, as I am too, I think. We both received good private educations as children and we are able to communicate our knowledge now.

When we were children . . . when we had money. “Money,” I said to Mister Potter. “Hard money is the only answer.” This was after I had managed to extract from him a pound of sugar, ten pounds of pork, ten pounds of wheat flour, a sack of assorted and unmarked vegetable seeds and the end of a bolt of white muslin—all the while ignoring his lamentations on the lack of any of those articles.

I returned to the school by the way I had come but with even more difficulties and delays than in the morning. This time, of course, I was moving against the traffic and even Southern soldiers, I found, were reluctant to move off the boards and into the mud to let a lady’s carriage pass, especially when they had a battle on their minds.

I was cursed audibly several times, once or twice by officers, and at one point of absolute impasse, it seemed as though the cart and Dolly and I might be overturned. Then a cadaverous, tobacco chewing soldier in a tattered straw hat came to my rescue. “You’re keeping North Carolina troops from the war, ma’am,” he said, taking Dolly’s bridle

and leading us on to a stretch of fairly dry ground. “But there’s some of us don’t mind a little interruption.”

“You stay with me now,” I told him, “until we come to a less crowded part of the road.”

“Yes ma’am,” he said genially. “I’d rather be goin in this direction than the other anyway.”

The firing to the east had become much more intense and rapid now. “Most of that ain’t cannons,” said the North Carolinian, in answer to my question. “That’s about a million Springfields and Enfields and squirrel guns all goin off to once. There couldn’t be much artillery in that band concert cause they say that brush is so thick up there a man has to go into battle sideways just to get himself kilt. That’s why the Confederate Army likes skinny volunteers like me.”

He stayed with us all the way to the Cedar Hill crossing and even led us part way up the side road until we were out of the path of the marching columns. Then he winked and saluted and started off, but I called him back.

There was a small piece of salt pork in my parcel, separated from the large slab. “Here,” I said, “for your trouble. The next time you come up here for a battle, try to let us know in advance and we’ll clear an open space for you.”

“You’re a joker too, ain’t you, ma’am,” he said grinning, “as well as bein a lady who knows exactly what she wants. I noticed that about you when I seen you comin down the road expectin the whole army of Northern Virginia to divide before you like the Red Sea. Well, that’s the way to be. Know exactly what you want . . . and to blazes with how you get it . . . and with everybody else.”

He fell back into line then and moved off, chewing philosophically on the raw chunk of pork. I often wondered after if he knew what he wanted and if he stayed alive to realize it. Some of his fellows stared enviously at him and then hopefully at me as they went past but I had no more meat to spare. I had the school to maintain and keep in operation until a better time. I had young girls to shelter and provide for and shield from harm. Let the generals and the politicians take care of everything else. The school was my first and only responsibility.

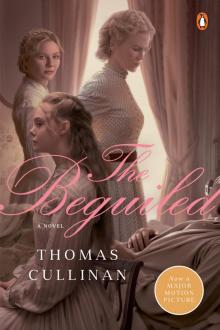

The Beguiled

The Beguiled